Some words about Stefano, by Braden Phillips

Although I grew up in Manhattan, the city always felt just outside the sanctuary of my relatively quiet neighborhood in Peter Cooper Village, a housing project on First Avenue between 20th and 23rd Streets. It bellowed and fumed over my shoulder, an infernal machine full of divine promise. It’s no surprise the atom was first split in the U.S. in a laboratory on the corner of Broadway and West 120th Street, releasing its titanic energy. New York is a kind of breeder reactor of human possibility, where incalculable volts have been produced over the years, for better and for worse.

I felt its presence mostly in fleeting moments rather than major events. Nothing filled my heart more with the grandeur of New York than the early Sunday morning drives in my father’s 1969 Pontiac GTO convertible as we headed up Park Avenue. In the open air and emptiness of the hour, the street felt like a runway for my imaginary flights into rarefied worlds of opulence and sophistication. A visit to my father’s Midtown office could ignite erotic fantasies if the Rockettes were rehearsing outdoors that day. From his window I could look down onto the roof of Radio City Músical Hall and see those divinely long-legged girls practicing their synchronized magic. I remember the black, turgid water of the East River a block away from my apartment, and the sight of its barges and bridges. The world wanted in – it never stopped coming – but I was lucky enough to already be there.

Perhaps more than any other city, New York has achieved the status of a living myth. Everything answers to its alchemical power: the small melds into the grand and the grand into the small, like an epic pointillist painting. The greater one’s vision for this alchemy, the more you recognize how each moment belongs to the greater whole.

You can find these moments in Stefano Buonamici’s photographs of New York, taken over a roughly two-year period, starting in October 1999, when he and his partner, Cristina Rius, lived in Bensonhurt, Brooklyn. More than 90 images are presented in this show, divided into two sections – two-thirds of them in “Before the Fall” and the rest in “On Parade.” Of those images, over 50 are reproduced in the exhibition catalog.

Together they create a portrait of a city in full stride just before disaster strikes, like a happy family on its way to a favorite familiar place when their car is suddenly broadsided by a speeding drunk. The attack that brought down the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center traumatized most people everywhere, especially New Yorkers, and above all those who lost friends and family.

Individually, all of these photographs (except for those that contain the Twin Towers) could have been taken after September 11; collectively, however, they evoke the gestalt of another time, with its simpler and surer state of mind. So is the purpose of these pictures to show us what we have lost? In his forward to A Way of Seeing: Photographs of New York by Helen Levitt, James Agee says Levitt’s work could “illuminate and enhance our ability to see what is before us and to enjoy what we see, and could relate all that we see to the purification and healing of our emotions and of our spirit…”

These photographs provide a similar kind of affirmation, allowing us to appreciate what is around us in a way that we might not have before the towers fell – the fabled silver lining behind every great loss.

The common denominator to Stefano’s work is a great sense of humanity, what he describes as “a willingness to happily let himself be taken” by what sees, allowing people and places to speak for themselves. “The main reason why I chose this profession is exactly because it lets me work without prejudices and preconceptions,” he says. Admittedly it’s a reach to make the connection with Stefano’s upbringing in Florence, Italy (he was born in Milan), but it’s worth a try. Florence was the birthplace of Renaissance humanism, where 14th century writers and artists, led by the likes of Petrarch and Giotto, made human worth and individual dignity a central feature of their thinking. Let’s just say that if modern-day Florence has retained some of its Renaissance ideals, Stefano has found a way to apply them to his New York photography.

Stefano’s work here shows the maturity gained through his trip to Iraq in early 1998, which represents a watershed event in his career as a photojournalist. At that time, crippled by an international embargo, life in Iraq was very hard for most of its people. With the publication of his photos in Max, a youth-oriented magazine published by Rizzoli Group and the Milan-based newspaper Corriere della Sera, Stefano found his work in greater demand at other top publications in Italy. The opportunity to document the little-known struggles of Iraqis reinforced Stefano’s commitment to photography, which he subsequently pursued with “more and more enthusiasm and dedication.” He also met his future partner, Cristina, in Iraq, where she was working as a correspondent for Barcelona’s Avui newspaper.

Stefano and Cristina moved to New York in 1999, making the commitment to a place both had known as tourists. To the photographer with an eye for the human condition, New York offers unique possibilities. Take Stefano’s shot of elevator riders at Macy’s Department Store, for example. Where else can one find the same collection of people, dressed as they are and wearing those expressions, as in this photograph? Say what you will about the melting pot theory of American society, but in this elevator the melting pot is alive and well. New York demands coexistence because there is no other choice, and by demanding it gets more of it than most other places. The body language of this moment could not be more eloquent. Indeed, as a city of crowded elevators and public transportation, New York has created its own school of choreography in tight spaces.

If you wanted to bring together 10 pictures that capture what was behind Wall Street’s most recent mania for quick profits, culminating in the current subprime-mortgage meltdown, you would have to include Stefano’s shot of two 20-something brokers. I call them brokers without knowing it for a fact, but if they aren’t they have clones who are. Two cockier neophyte capitalists, obsessed with weight lifting and six-figure salaries, would be tough to find.

And there is a kind of New York haiku in the pairing of the lovely photograph of a young Chinese woman peering out of a building and the luncheonette with its grease- and neon-stained workers. They look world’s apart but in New York you don’t need editorial license to find them right next door to each other.

Perhaps more than any other pictures, those of New York’s after-hours clubs demonstrate Stefano’s artistic talent and journalistic temperament at their best. It’s not just a coincidence that the single most common theme to his assignments over the years has been the nocturnal habits of the young. He has traveled from Barcelona to Beirut to unearth these secret worlds – at least to the uninitiated – a task that requires special skills. “In all these assignments my job was to discover the fascination of the local nightlife and the characters who moved in it,” he says. “I had to develop an attitude for approaching each world and a dialogue to get close to my subjects in order to get shots that are natural and relaxed.”

Stefano found New York’s S&M clubs to be the most challenging of his after-hours explorations. Only two photographs from this series have been included in the show, and, sadly, some of the others were lost in his move from New York to Barcelona.

Parades, that most photogenic perennial of New York life, are justifiably given a section of their of own in this exhibit. As an outsider looking in, Stefano hits several iconic bull’s-eyes, such as the radiant, white-hatted girls marching down Broadway in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. You can feel their utter joy and realize that not any parade in any city can produce that kind of wholehearted abandonment: it takes a street like Broadway, a blazing autumn sun, cheering thousands and sheer scope – American pageantry as only New York can do it.

This and many other pictures in the “On Parade” section look timeless because they are. But a few stand out for more distinctive reasons, particulary the black woman standing front and center in the shot of spectators at the Hare Krishna Parade. Her directness is also evocative of the New York character, which is nothing if not direct.

It’s taken eight years for Stefano to feel it was appropriate to put his parade pictures on display. Their celebratory tone clashed with the sadness produced by September 11. Now, however, he sees them not only as the testimony of a time, but “the key for reading my photographic work.”

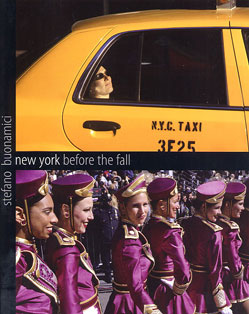

It’s not often that a photographer can point to one picture out of more than 90 and say that’s it: that’s the masterpiece of the lot for me. For Stefano, the woman in the yellow taxi, taken on the fly just outside Central Park, is “the perfect image I had always been seeking.”

“It has movement, dynamism and I recall having only seen the person vaguely, looking at the sun, very enigmatic,” he adds. “Whoever sees it is prompted to read something into it, including that it is someone famous or someone whose gender is unclear. At the time I thought that maybe it was a passing angel.”

Braden Phillips

Braden is an American author and journalist based in Barcelona, Spain.

“New York Before the Fall” is an exhibition of color photography taken during the two years I spent in New York, from 1999 to 2001. The work displays a confident and optimistic nation, in command of its own destiny and proud of its identity, the image of an America that tragic events would soon contradict. In light of the tragedy of the Twin Towers and the current economic infirmity that grips America, from where it has spread to the world at large, this emblematic journey underscores the uncertainty of future prospects.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!